“¡Dense cuenta que estamos regresando a lo mismo, a las haciendas!”

(Realise that we are heading back towards the same (situation), the haciendas!)

Neighbour in Pachacutec District (27 April 2015)

Provision of drinking water is currently recognised as a human right. However, in Peru, as in many countries, the human right to water, and water security in general, does not appear on the public agenda unless it is indirectly associated with other current policies.

In April 2015, as we continued with our research on the energy-water-food security nexus in the inter-state Ica Basin, we encountered another issue of deep concern expressed by local people in the valley: drinking water. Aquifers, besides being the main source of water for the agro-exportation system, are also the primary water source for human consumption in many towns, especially those on the outskirts of Ica city, such as those in the Pachacutec district.

The Pachacutec district, named after the Inca builder of the La Achirana irrigation canal, is a landscape of large agribusiness farms that utilise groundwater 24 hours a day, as well as small and medium-sized farms that rely more heavily on surface water from the Ica River. Despite being surrounded by two irrigation canals, La Achirana and La 75, more than 6,000 people in Pachacutec have a restricted water supply. Homes currently have access to drinking water every two days and for less than four hours.

Water insecurity, specifically domestic water, was a persistent challenge for everyone we visited in this district on the city’s periphery. Even though the region’s water scarcity is well known, it seems the situation gets worse at the margins. Here, we can see how institutional discourses about the primary use of water (for human drinking purposes) are overshadowed by market discourses, where water has long been a commodity. Nevertheless, drinking water services have always been a subject of intense debate, especially its profitability and privatisation. In this context, we add the complex dynamic of use priorities that arise where water is in dispute among sectors.

During the 1990s, with the neoliberalisation of the Peruvian economy, the political move to attract domestic and foreign investment was accompanied by flexible private property laws that included natural resources. This legal and economic context facilitated the growth of agro-industrial exporting companies in arid areas such as the Ica Valley. During this period, extreme and rapid changes occurred in the water supply and sanitation services in the arid, coastal regions of Peru.

In this decade, privatisation of land and natural resources was outlined as a unique solution for Peru’s financial collapse, and the water services sector was also included. Rejected by the majority of citizens, management of water and sanitation services was finally transferred to municipalities in a process that lacked a clear strategic plan. This responsibility was an immense challenge for many municipalities, especially those that were small, relatively young and without adequate training or budgets to manage these services. In the meantime, local water management systems, known as Juntas Administradoras de Servicios y Saneamiento (JASS) (management entities for service and sanitation), were created to provide this service in small towns, supported by local governments.

Beneath the arid land of Ica lies one of the largest aquifers in Peru: the Ica-Villacurí Aquifer. Groundwater in this region is the primary water source; groundwater extraction began in the 1920s and intensified in the following decades to supply agro-export farms and human populations alike (Oré, 2005). Groundwater abstraction was promoted by the government to counteract the effect of prolonged droughts on surface water supplies. Groundwater use has also intensified without precedent. The absence of groundwater monitoring and regulation systems has resulted in deepening water levels and dry wells for farmers and urban residents alike. At present, the aquifer is in a state of overexploitation to the degree that a state of emergency has been declared.

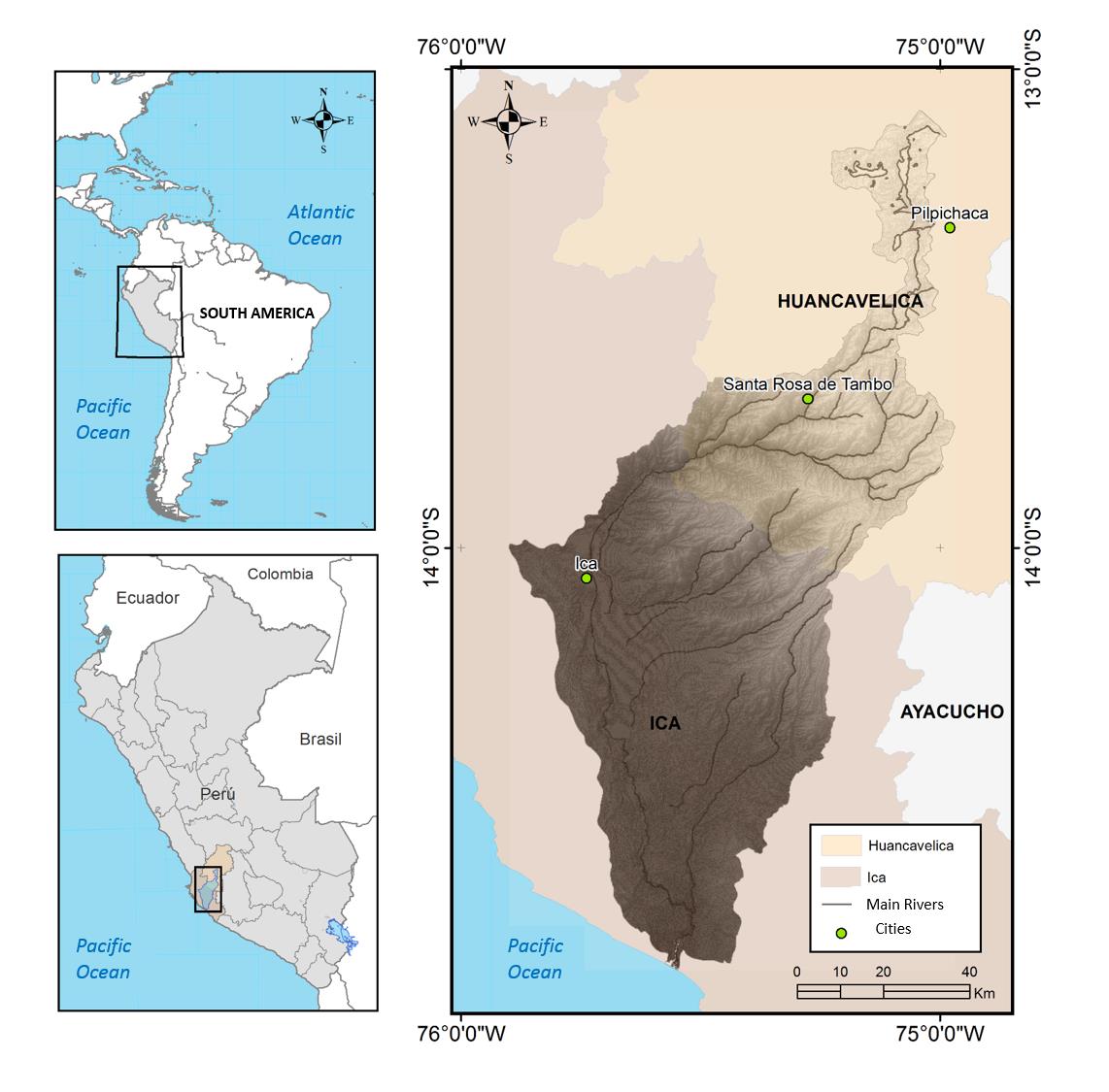

Large-scale interbasin transfer projects were also promoted to bring more water to the thirsty Peruvian deserts. The Ica Basin spans two states in Peru: Ica and Huancavelica. The latter is a highlands state of extreme poverty and isolation. Government supported projects in the region have included efforts to collect water in high altitude lakes that naturally flow east, to the Amazon, and divert flow through tunnels to the arid, Pacific coast. Not accounting for the ecological impacts of diminished in-stream flows, residences of Huancavelica have also suffered as water supplies are diverted to supply large and small farms in the Ica Valley. These flows provide longer and more reliable surface water to farmers, but the agro-export industry has outgrown even these supplies. Current discussions are underway to expand these interbasin transfer projects in the highlands to supply the growing coastal demands.

These events have had a direct impact on the access to drinking water for the local communities. As the agricultural industry has grown so have the coastal populations, as people are drawn from impoverished regions in the highlands to the economic engines of the coast. The Ica Valley has experienced multiple physical and social transformations, and urban development has expanded rapidly, especially on the peripheries as people are drawn to work on the farms and in the packing warehouses. However, basic services such as drinking water supplies have not kept pace, especially in these suburban shanty towns and rural areas.

“We don’t have water the full day, it’s just for hours. We are suffering; we have one hour each per sector to collect it [our water]. Ideally, you should have a water tank at home.”

Mr. Hugo, resident of Pachacutec

Groundwater managers face multiple challenges to provide potable water to the people of the Ica Valley: high salinity concentration, high energy costs and demands to pump groundwater, the deteriorating condition of the wells, the deepening levels of the aquifers, and the large number of users that exceeds the wells’ capacity, as well as other issues.

“We don’t have continuous potable water. Water [tap water supply] is alternated, one day yes, one day no; by hours. It starts at 6am and finishes at 9am. It’s because we are many neighborhoods, and they have to attend everyone, and water is scarce – what can we do? At least we have water, but in Pachacutec, they drink salty water.”

Mr. José Hernández, Tate District

In recent years, the government has made a big investment in infrastructure to increase access to drinking water and sewage services. According to statistics from the Ministerio de Vivienda, Construcción y Saneamiento, more than 85% of Peruvians have access to water supply. However, as is evident in the Pachacutec district case, there is more hidden behind these numbers; infrastructure is just one approach to reach equitable and efficient distribution of water. Governance and water management are quite another issue.

Water governance should be considered in the water management agenda to include increasing support for local organisations, capacity building, and an increase of stakeholder participation from diverse institutional levels. In addition, water governance should include collective action and more equitable, efficient and sustainable management at different scales. But there seems to be something missing that is crucial for social equity: natural resources should not be considered private property because their management and sustainability are left to the vagaries of the market. Investment might not be enough to provide drinking water to the people in the Ica Valley; a political and social commitment on behalf of diverse scales, conscious of social, economic and environmental interrelationships, might be the start.

References

Oré, Maria Teresa. Agua. Bien común y usos privados. Riego, Estado y conflictos en La Achirana del Inca. Lima: Fondo Editorial de la Pontifica Universidad Católica del Perú; Universidad de Wageningen y Soluciones Prácticas (ITDG), 2005.