There is an interesting question being posed in the corridors of power. Can the Cape Town water crisis happen in Pietermaritzburg and Durban and, if so, what should we do to avoid it? This formed part of the deliberations by the Ministerial Technical Committee (MinTech) that advises the Minister of Environmental Affairs at a national level. Recently, I was asked to contribute to a report on the subject. What follows is a summary of my contribution.

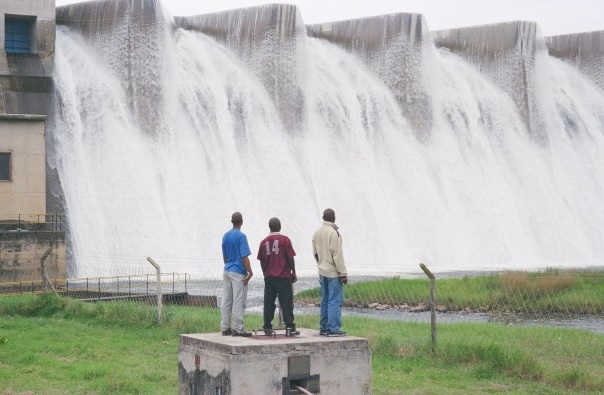

In April 2016, the Spring Grove transfer scheme which brings water from the Mooi River to the uMngeni was commissioned. In the six months that followed, Umgeni Water pumped 62 million cubic metres of water through the system into the Midmar Dam. That is over 300,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools – a lot of water.

At the time, Midmar was about 40% full with little natural inflow. If that water had not been pumped across, its level might have dropped to below 20%. If the drought had persisted for another year, we would have had a full-blown crisis. But the main contributor to the crisis would not have been the drought, but the leaking pipes in Durban, Pietermaritzburg and surrounds. Recent information from the national Department of Water and Sanitation indicates that South Africa is leaking about 35% of its water supplies.

With Umgeni Water supplying 400 million cubic metres per annum, this would mean that about 140 million cubic metres is lost through leaks – which is more than is gained through the transfer scheme!

However, even if we fixed most of the leaks and focused on improved water conservation, there is another problem – a crisis here that is rapidly growing to the scale of what Cape Town is experiencing but it takes a different form and is unseen, invisible. This is not a crisis of quantity but a crisis of quality. Much has been made of the continually declining water quality in the Msunduzi River and in the past I have written about ‘paddling in poo’, but it is not only about the Msunduzi. At the risk of being alarmist, the entire river basin is drowning in animal and human faeces.

In the upper and middle reaches of the basin there is a steady intensification of livestock agriculture, mainly beef, dairy and piggeries. The nutrients generated by these operations are contaminating Midmar directly through the uMngeni and indirectly through the transfer scheme. In addition, Midmar is being contaminated by sewer failures in Mpophomeni.

Albert Falls Dam is being contaminated by semi-treated sewage from Howick, and the Inanda Dam is being contaminated by sewage from Pietermaritzburg. All three of our major supply dams are being subjected to significant and, in my view, criminal abuse. What compounds this is that when these systems are at low levels there is less water so their ability to dilute these nutrients is greatly reduced. We are already seeing the impact, especially at Inanda Dam, where blue-green algal blooms and the massive spread of water hyacinth are affecting users in numerous unpleasant ways.

So, we have a crisis but it is not a crisis generated by drought or floods or climate change. It is generated by us, by our actions, and we will only emerge from this crisis through our own actions.

What should we be doing to get out of this crisis? In the short term, we need rapid executive action that fast-tracks the new Mpophomeni wastewater works and the upgrades to the Howick works, fixes the sewers of Pietermaritzburg, and that halves the leaks from our water pipes. If Msunduzi is unable or unwilling to fix the sewers, let Umgeni Water do it – the offer has already been made.

We need to reverse the trends, and have a few small quick victories, even if it is only to restore morale in a very demoralized system.

Duncan Hay is Executive Director of the Institute of Natural Resources.