acequias along the street irrigating trees (Photo: R. Varady)

I was fortunate enough to be invited to participate in the 2nd International Congress Water for the Future that was held in Mendoza, Argentina, on 7-9 March 2019 – my second visit to the city. It was great to be in Mendoza again and visit our Argentinean colleagues from the National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET). This time, my visit coincided with the wine festival, or Vendimia, which is a week full of parades, shows, and events related to grape harvesting and wine production – the main economic activity of the region.

A dozen of our partners from all over the continent participated in this event, as part of the International Water Security Network (IWSN) project and AQUASEC – Center of Excellence for Water Security. The congress was organized and hosted by the provincial water authority – the Departamento General de Irrigación (DGI), with which IWSN has collaborated for the past six years.

During this congress, I gave a talk about green infrastructure in Tucson, Arizona, a U.S. city that is a leader nationwide in terms of policies that support this type of infrastructure. Like many cities in the world, Tucson is investing in greening projects to help its residents adapt to climate change – by providing shade that can alleviate heat, and by managing stormwater flow and reducing flooding risk.

However, implementing green infrastructure widely in cities is not easy. Professionals and practitioners around the world face many challenges, including design standards (how to build the most efficient infrastructure?), regulatory (what policies are needed to promote green infrastructure throughout the city?), financeability (who pays for this type of work and its continuous maintenance?), socio-economic (how to include underserved communities in the distribution and procedures of greening projects?), and innovation (how to identify and adopt innovative approaches?).

Museum, photo: A. Zuniga)

The city of Mendoza seems to have largely succeeded in addressing these challenges. As with my first visit, I marvelled at the amazing water infrastructure that runs along all the streets and irrigates the city’s 50,000 or so magnificent trees every day. The trees in Mendoza, as well as the parks, boulevards, plazas, and the acequias – or canals – that water them, are the most distinguishing architectural feature of the city. Walking around the streets in Mendoza you can easily forget that you are actually in a desert environment (average annual rainfall is about 220 mm). The fully-grown trees (poplar, platanus, mulberry, sycamore, Russian olive, elm, ash, linden, acacia, and others) are the result of a century of irrigation. How did Mendoza begin to address the challenges for the wide implementation of greenspace?

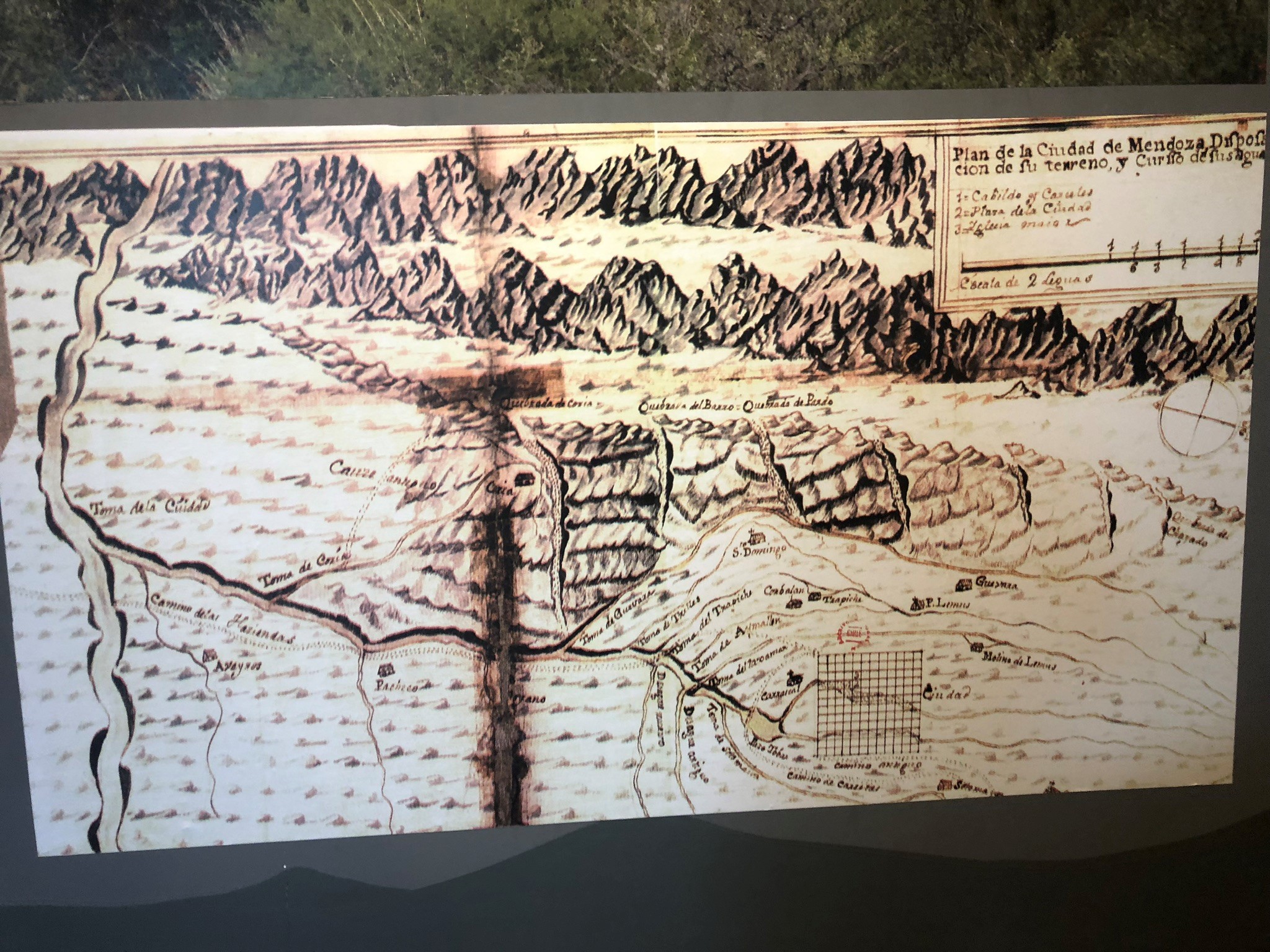

The story of greenspace in Mendoza goes back to pre-colonial times when the indigenous people, the Huarpes, dug the original acequias to direct surface water from the Mendoza River (and other rivers) to irrigate agricultural fields. Located in a semiarid region, Mendoza is fortunate to have a relatively reliable source of surface water that comes from snowmelt in the Andes mountains. When the Spaniards arrived in the 16th century, they destroyed most of the indigenous culture, but not the acequias. They recognized the value of this type of water infrastructure that allows human life in the desert. The Spanish conquistadores (conquerors), maintained and reorganized the acequias so that these continued to supply water to Mendoza.

from Mendoza’s Foundational Museum)

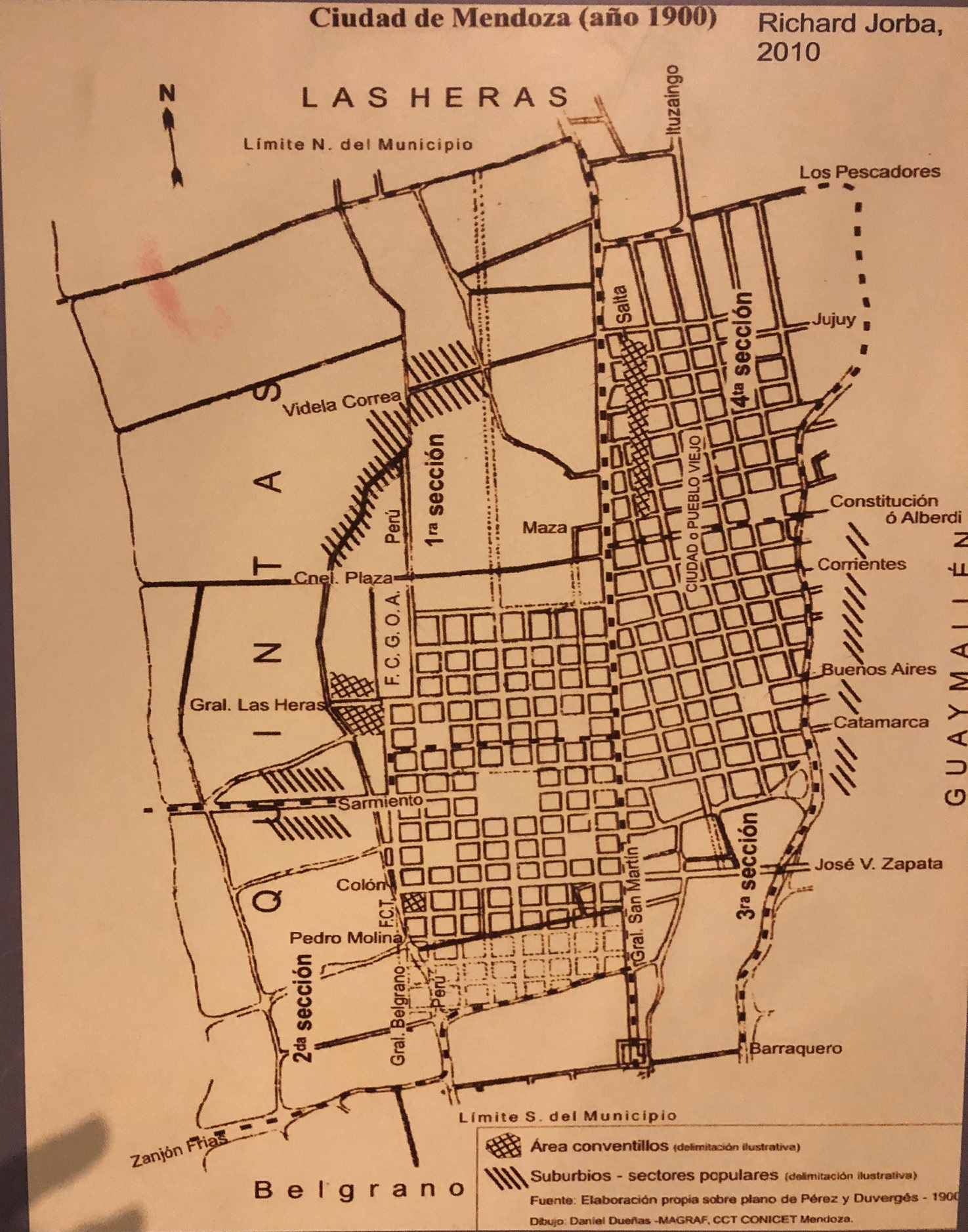

On 20 March 1861, a disaster hit the city. A powerful earthquake hit Mendoza and destroyed most buildings, a fire consumed the few buildings that were still standing, and obstructed aqueducts caused flooding. This original area of Mendoza is now known as ‘La Ciudad Vieja’ (The Old City). ‘La Ciudad Nueva’ (The New City) was built in 1863 along the property line of the old Hacienda San Nicolas – a neighboring farm located on slightly higher ground. The design of this modern city addressed public health concerns about toxic air, that was thought to cause diseases, by opening streets to air and light. Although nowadays the streets are sometimes completely shaded by the tree canopy cover, back then, the trees were not fully grown, and sunlight filled the streets of Mendoza. The new urban design also incorporated infrastructure for different modes of transportation and water systems – potable, stormwater and wastewater. The new city is characterized by the features that we find today in Mendoza including the tree-lined streets, plazas, parks, boulevards, and of course, the acequias.

Museum)

For the first time in the history of Mendoza, vegetation acquired an aesthetic value and became the proud identity of Mendoza, or ‘The Forest City.’ The constant flow of water is now controlled by strategically located gates that are opened for certain periods of time, depending on the water allocation – or the agreed volume of water that corresponds to a particular water use. The slope of the terrain does the rest of the work, as gravity pulls water with a constant flow to run through the city and, more importantly, along the roots of the aligned trees. However, the functioning design of this water infrastructure was not successful in the beginning. Stagnant water in some sections of the city used to invade the air with foul odors, and this was thought to cause diseases.

To correct this flaw, the design standards for Mendoza have been changed by trial and error over time. Nowadays, the acequias work for the most part (carrying flowing water), except when there is a flood event, or when the acequias are blocked by trash that nowadays includes plastics. Innovation is needed to address these remaining design issues.

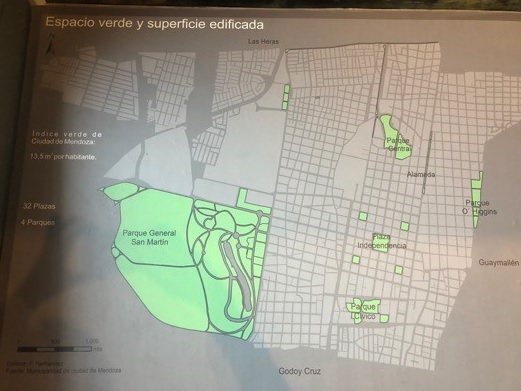

Nature in Mendoza serves more purposes than mere aesthetics. Although not frequent, there are flood episodes in Mendoza known as aluviones, when the river floods and carries vast volumes of sediment, severely damaging the urban infrastructure. In addition, every now and then, there are winds, known as vientos sonda, that hit the city. These winds are unusually hot and sandy and affect the health of the population. To protect the city from these events, and for sanitation reasons, two parks were built – the West Park known today as the General San Martín Park; and the East Park, known today as the O’Higgins Park. The parks and plazas significantly improved the air quality of the city. The San Martin Park was designed by the famous French-Argentinean landscape architect Carlos Thays, who also designed several parks in Buenos Aires. His design of the San Martin Park followed the English and French landscape design principles of the 19th century that include promenades with sculptures, a rose garden, and splendid fountains. Nowadays, the 971-acre park also includes a stadium, a university, CONICET offices, and an amphitheater – where the main event of the Vendimia took place.

Museum)

In addition to enhanced aesthetics, flood control, and air purification, open spaces were used as refuges. To protect the citizens from anticipated earthquakes, plazas were built across the city. This way, nature is used to enhance urban resilience in Mendoza. The city’s urban reforestation program was legally supported by the Provincial Law No. 19, signed in 1896. This law addresses the regulatory challenge of greening projects – to develop policies that support these types of initiatives. However, regulations for new development are still needed as residential development in the urban fringes of the city does not include these natural elements, exposing the residents to aluviones and harmful winds.

The DGI, the water agency of the province that hosted the congress, is the organization that manages and maintains the acequias. The water used for the irrigation of trees, parks, and plazas in Mendoza is considered a ‘recreational use’ and is part of the water budget of the region. Most people support this water use because it allows the beautiful vegetation in the city to thrive, addressing the financeability challenge of greening efforts. However, during the current uncertain times of climate variability, when uses of water are heavily contested (agricultural, municipal, industrial, and recreational), the future of recreational uses of water is being questioned, as is the use of non-native plant species. Sustainability arguments push for the use of native desert species and less water used in the irrigation of landscapes.

It will be interesting to see what the residents of Mendoza decide is more important and valuable – use water for the irrigation of more vineyards, municipal growth, or industry? Or to keep maintaining their greenspace?

For now, at least, in Mendoza there seems to be wide support for and pride in the trees and greenspace that enhances the quality of life of the residents. According to Ricardo Ponte in his 2005 book De los caciques del agua a la Mendoza de las acequias (‘From the chieftains to the Mendoza of the acequias’), the reason most people in Mendoza are aware of the vital importance of water in this region and the aesthetic value of trees is because of the acequias that support the trees and allow people to see and feel water running in front of their own homes every day. Unlike most cities in the world, water infrastructure in Mendoza is not buried underground; instead, it is an essential part of the urban fabric and the daily lives of its residents.

In my opinion, Mendoza would not be Mendoza without its beautiful trees. I think the recreational use of water should be maintained, especially under climate change conditions. Trees not only beautify the city, but they also alleviate heat, flooding, and other hazards. In the words of Daniel Ramos Correa, a famous architect in Mendoza during the 1980s: “The best architect of Mendoza is the tree.”