After a year-and-a-half of planning, the University of Arizona hosted a conference on science and diplomacy on 22-24 February 2017. The Udall Center for Studies in Public Policy, as a partner in the LRF-supported International Water Security Network, was a key co-sponsor of the event. Prof. Robert Varady, PI of the Americas component of IWSN, and his Udall Center colleague, Prof. Andrea Gerlak, were members of the organising committee.

After a year-and-a-half of planning, the University of Arizona hosted a conference on science and diplomacy on 22-24 February 2017. The Udall Center for Studies in Public Policy, as a partner in the LRF-supported International Water Security Network, was a key co-sponsor of the event. Prof. Robert Varady, PI of the Americas component of IWSN, and his Udall Center colleague, Prof. Andrea Gerlak, were members of the organising committee.

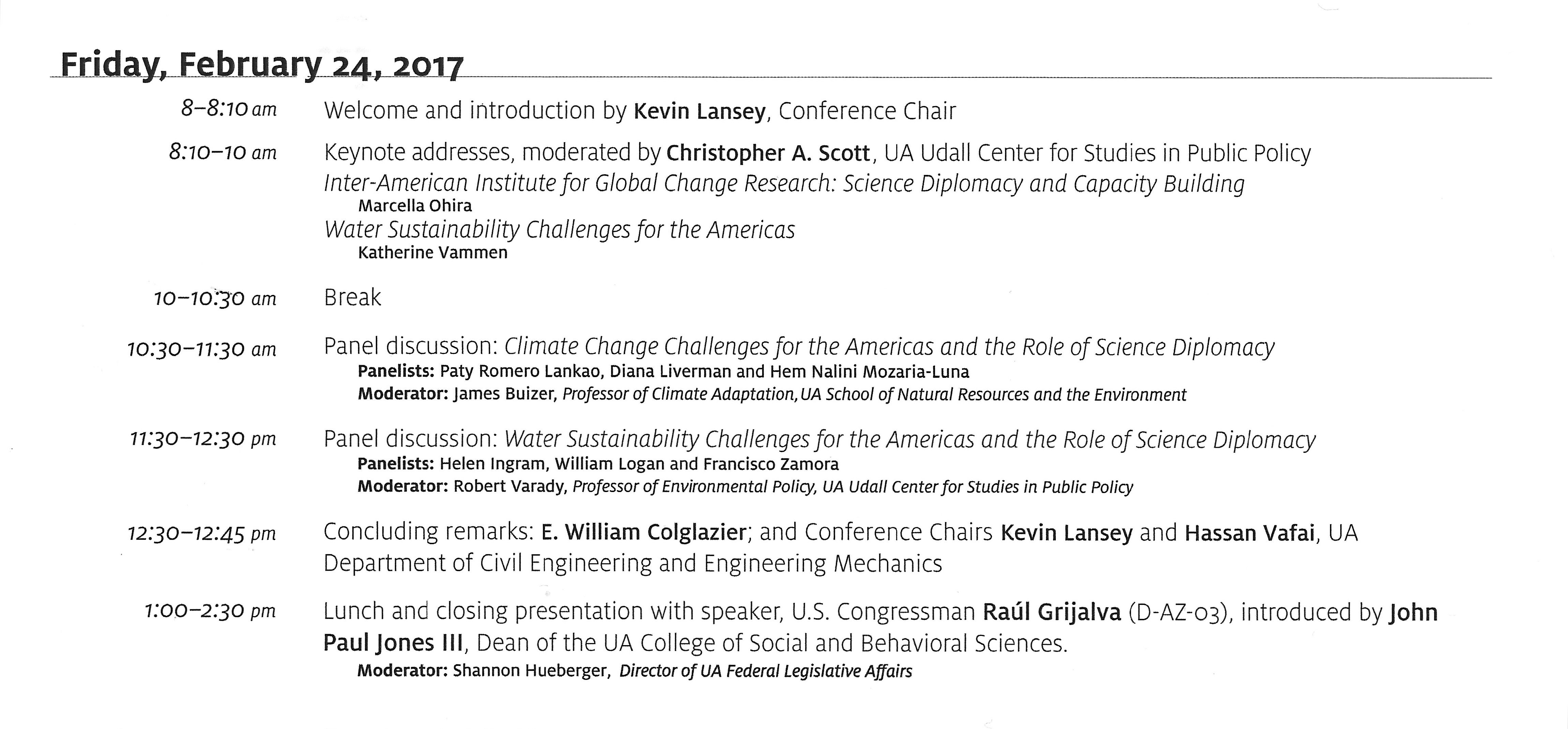

The event, which drew nearly 150 attendees and participants, opened with a broad purview, featuring some very distinguished speakers with science-diplomacy experience dating several decades – including a Nobel Prize-winning medical scientist, the current science advisor to the U.S. Secretary of State, and two of his predecessors (see article below by Jill Goetz). The second day, mostly organised by the Udall Center, directed attention to issues relating to water and climate in the Americas.

The event, which drew nearly 150 attendees and participants, opened with a broad purview, featuring some very distinguished speakers with science-diplomacy experience dating several decades – including a Nobel Prize-winning medical scientist, the current science advisor to the U.S. Secretary of State, and two of his predecessors (see article below by Jill Goetz). The second day, mostly organised by the Udall Center, directed attention to issues relating to water and climate in the Americas.

*

(The following article about the conference was written by Jill Goetz and first published on the UA News blog here.)

In times of diplomatic turmoil and combative negotiations, scientists and engineers will continue solving problems and seeking the truth, speakers affirmed at a recent summit on science diplomacy and policy co-sponsored by several University of Arizona colleges and programs.

“When others deny climate change, ask for the evidence,” said Norman Neureiter, a former staff member in the White House Office of Science and Technology and the first science and technology adviser to a secretary of state.

“It is scientific evidence that is essential for setting sound policies,” Neureiter said. “Science is how we know the truth, how we understand the natural world. It is not an ideology.”

Neureiter spoke at a panel held Feb. 21 to kick off the “Science Diplomacy and Policy With Focus on the Americas” conference, which centered on climate change and water sustainability in the Americas. Neureiter was involved as an interpreter in private discussions with scientists on nuclear weapons testing with the former Soviet Union in the 1960s and as a participant in semiconductor negotiations with Japan in the late 1980s. Scientists and engineers played a critical role in reaching final agreements, he said.

The conference was co-sponsored by the UA College of Engineering, Office of Global Initiatives and other programs and chaired by Kevin Lansey, head of the UA Department of Civil Engineering and Engineering Mechanics.

“We have a responsibility to share our knowledge with people in countries throughout the world, whatever our diplomatic relationships may be,” said Peter Agre, recipient of the Nobel Prize in chemistry, who has led scientific delegations to Cuba, North Korea, Iran and other countries that have strained or nonexistent diplomatic relations with the U.S.

Agre, director of the Malaria Research Institute at Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, shared stories and slides from his research programs to eradicate malaria in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Zimbabwe and other African nations with authoritarian regimes.

“These countries are rich in terms of minerals, but they bear a staggering burden from malaria, which kills approximately 400,000 children each year worldwide,” he said.

Agre offered a rare glimpse inside North Korea, which he has visited three times as head of delegations for the American Association for the Advancement of Science to teach students, meet scientists and facilitate research collaborations at Pyongyang University of Science and Technology.

“We shared stories about our research and hopes for our children and our grandchildren,” said the former president of the AAAS. “Friendships can make a difference.”

Agre met with Fidel Castro as head of a U.S. scientific delegation to Cuba in 2011. “There were obviously many things we disagreed on, but Castro understood that science would play an important role in advancing Cuba’s economy and lifting its people,” he said. “That was one thing we could agree on.”

In 2012, Agre led a AAAS delegation to Iran. “Overall, it was a very positive visit,” Agre said in an article for AAAS. “Our meetings with faculty and students were always positive — it seems to me that we all have a lot to share. … From a scientific viewpoint, the doors are certainly open.”

When tensions did arise, the delegates focused on constructive science engagement.

“We weren’t there to apologize or criticize. We were there to talk about science and to find common ground,” he said.

Thomas R. Pickering, vice chairman of a consulting company and former U.S. ambassador to seven countries — including the Russian Federation and Israel — and the United Nations, had to cancel his planned trip to Tucson to participate in the panel. So his address about his storied career spanning six decades was delivered via video.

In introducing him, E. William Colglazier, a former science and technology adviser to secretaries of state Hillary Clinton and John Kerry and the honorary chairman of the UA conference, called Pickering the “premier and most well-connected American ambassador of our time.”

Pickering, a participant in some of the most consequential diplomatic developments of the 20th and 21st centuries, considers the Iran nuclear agreement an important contribution to science diplomacy.

“This agreement might become the international gold standard for reaching agreements with developing nations,” he said. “It calls for surveillance from uranium mining extraction to disposal of spent fuel rods and ensures 24/7 knowledge of what is happening in the Iran nuclear program. It highlights the need for acceptance to compromise, on both sides, and could be an important guide for future negotiations with developing countries.”

During a question-and-answer session at the conference, speakers expressed apprehension about how the Trump administration’s travel bans and proposed budget cuts might hamper scientific research and innovation.

“America up until now has been a haven for thousands of scientists and scholars who have come to the U.S. to escape persecution and conflict elsewhere,” said Neureiter, an adviser at AAAS. “They have made huge contributions to America’s technical and scientific excellence.”

He added: “I have serious concerns about threatened cuts in various government department budgets. America must not fall behind in scientific research, engineering and innovation. These disciplines are vital for the future growth of the U.S. economy and for the health and well-being of the American people.”

The conference also presented a rare opportunity for students to interact with important scientists and policy experts.

“Unless you are well-connected, most undergraduates miss out on great opportunities like this,” said Estefanie Govea, who has a UA bachelor’s degree in political science and is pursuing a second bachelor’s in environmental and water resource economics in the UA College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

Govea is one of several UA students, most of them in the College of Engineering, who served as rapporteurs and will write conference proceedings to be submitted to the AAAS journal — Science & Diplomacy — and ensure that all conference presentations are posted online.