de Grenade, Dr. Nicolás Pineda, Antonio Rodríguez, Daniella Yocupicio, and Flor Ibarra.

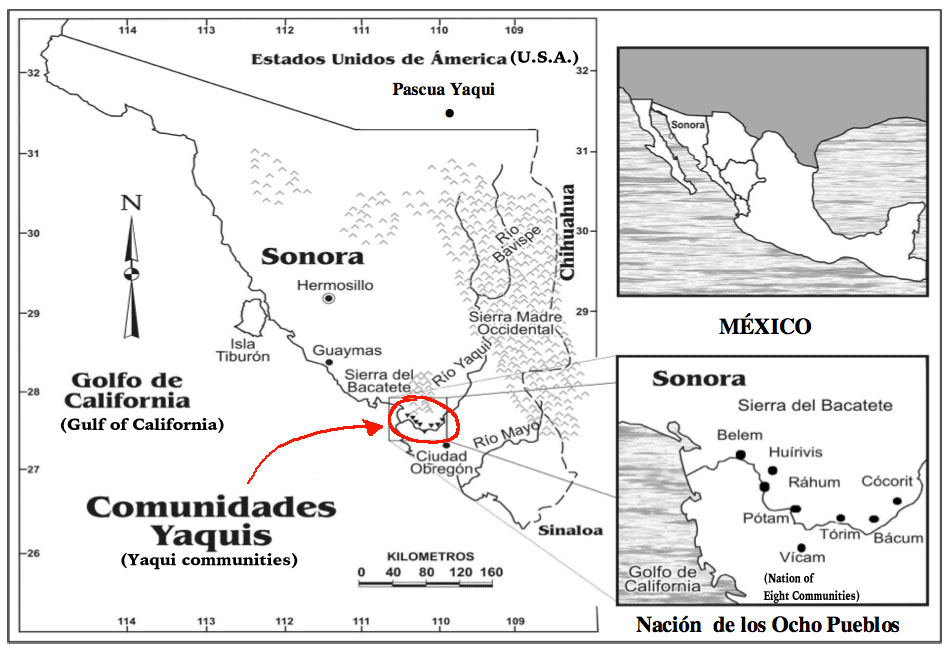

On 3 March 2015, we crossed an imaginary line into Indigenous Yaqui territory in the northern Mexican state of Sonora. Eight Yaqui villages lie along the lower bends of the Rio Yaqui, just before the river reaches the Gulf of California (also known as the Sea of Cortés). The Yaqui, or Yoremes are native peoples that traditionally called the lower Yaqui River Basin their homeland, and practiced agriculture on the fertile floodplains and fishing in the gulf. Many have been displaced by persecution in Mexico – in the early 1900s, during a period of war between Mexico and the Yaqui, a segment of the tribe emigrated to the southwestern U.S. There, the diaspora community known as the Pascua Yaqui, was officially recognised by the U.S. government (1978) and they now have a small reservation outside of Tucson, Arizona.

Though marginalised by the Mexican government and fragmented into communities in two countries, the Yaquis in Mexico have retained a thriving culture. The eight Yaqui pueblos (towns) of Potam, Vicam, Tórim, Bácum, Cócorit, Huirivis, Belem and Rahum have a cohesive spirit and vibrant traditions. This weekday during La Cuaresma, or Lent, is part of a syncretic religious tradition that incorporates traditional cosmology with the Catholicism introduced by Jesuit missionaries during colonial times. As Easter approaches, the festivities increase, with ritual dancing and penitence traditions.

Though marginalised by the Mexican government and fragmented into communities in two countries, the Yaquis in Mexico have retained a thriving culture. The eight Yaqui pueblos (towns) of Potam, Vicam, Tórim, Bácum, Cócorit, Huirivis, Belem and Rahum have a cohesive spirit and vibrant traditions. This weekday during La Cuaresma, or Lent, is part of a syncretic religious tradition that incorporates traditional cosmology with the Catholicism introduced by Jesuit missionaries during colonial times. As Easter approaches, the festivities increase, with ritual dancing and penitence traditions.

We drove with Prof. Nicolas Pineda and his team of undergraduate and graduate researchers from El Colegio de Sonora on a rainy day in the Sonoran Desert. We took the highway south from Hermosillo through the landscape of columnar cacti and palo verde trees, with the jagged horizon of blue mountains in the distance. Flor Ibarra, a master’s student in public administration spent part of her childhood in Yaqui villages, and she directed us off the main highway to the narrow paved, and then dirt roads toward the gulf shore and the mouth of the river. Sea birds from the Gulf of California swept over the pangas, or fishing boats, lined up along the shore.

We drove with Prof. Nicolas Pineda and his team of undergraduate and graduate researchers from El Colegio de Sonora on a rainy day in the Sonoran Desert. We took the highway south from Hermosillo through the landscape of columnar cacti and palo verde trees, with the jagged horizon of blue mountains in the distance. Flor Ibarra, a master’s student in public administration spent part of her childhood in Yaqui villages, and she directed us off the main highway to the narrow paved, and then dirt roads toward the gulf shore and the mouth of the river. Sea birds from the Gulf of California swept over the pangas, or fishing boats, lined up along the shore.

As part of his research with the International Water Security Network, Dr. Pineda and his students are designing studies to address domestic water access and vulnerability within the Yaqui pueblos. According to a 1940 law, created by reformist President Cárdenas following the formal establishment of the federal Indigenous reserve, the Yaquis have the right to 50% of the river’s flow. Since that time, however, the Yaquis have faced many challenges keeping their rights to the Yaqui River for agricultural and cultural uses. The 150km Acueducto Independencia, an interbasin transfer project, was completed amid controversy in 2013 to divert water from a dam on the Yaqui River in order to satisfy the growing demands of the region’s capital, Hermosillo. Today, the river supplies water for two irrigation districts that produce most of the country’s wheat, as well as Ciudad Obregon and Hermosillo. The Yaqui peoples belong to one of the districts, and many rent farmland to wheat producers.

As part of his research with the International Water Security Network, Dr. Pineda and his students are designing studies to address domestic water access and vulnerability within the Yaqui pueblos. According to a 1940 law, created by reformist President Cárdenas following the formal establishment of the federal Indigenous reserve, the Yaquis have the right to 50% of the river’s flow. Since that time, however, the Yaquis have faced many challenges keeping their rights to the Yaqui River for agricultural and cultural uses. The 150km Acueducto Independencia, an interbasin transfer project, was completed amid controversy in 2013 to divert water from a dam on the Yaqui River in order to satisfy the growing demands of the region’s capital, Hermosillo. Today, the river supplies water for two irrigation districts that produce most of the country’s wheat, as well as Ciudad Obregon and Hermosillo. The Yaqui peoples belong to one of the districts, and many rent farmland to wheat producers.

The Yaqui community has faced many challenges of land and water rights through their conflict-laden history with the Mexican Government. Today, those closer to the sea live from fishing, while those inland along the river farm, or lease farmland to produce the grains that have given the region its identity as the nation’s breadbasket. Though the region produces a wealth of its agriculture, many of the Yaqui live in extreme poverty. The Yaqui have long struggled with uneven development and incorporation into the Mexican state. Few have access to safe drinking water; agro-chemical use on the farm fields has had severe effects on health and childhood development in the pueblos; and the tribe struggles with lack of public infrastructure and high rates of infant mortality.

As we visited the villages and spoke with a few of the residents, the water security challenges became increasingly clear. A single water pipeline from a well services the villages, and has been subject to periods of shutdown both from power cuts and from damage to the system.

As we visited the villages and spoke with a few of the residents, the water security challenges became increasingly clear. A single water pipeline from a well services the villages, and has been subject to periods of shutdown both from power cuts and from damage to the system.

Each house in the villages has a spigot, and rather then indoor plumbing, residents stretch a single green garden hose to fill cisterns for domestic uses. Though some houses have internal toilets, washing machines, and sinks, most of these relied on exterior secondary pumps and storage tanks, or bucketing water by hand. Most residents have outdoor kitchens, and divert wastewater to irrigate fruit or ornamental trees around the homes.

While this system of water reuse reflects wise desert-water management practices, the standing water also provides mosquitos a breeding ground and perpetuates health challenges such as dengue fever in the villages. Most residents used outhouses, and many with whom we spoke complained of low water pressure in the water hoses that made it challenging even to fill the cisterns. Each village has an elevated water tank that at one point serviced the town, but few, if any are still in use.

As part of a broader assessment of water security in the Yaqui River Basin, Dr. Pineda and his students are working with tribal authorities and residents to better understand the challenges of domestic water access.