In recent years, Peruvian coastal valleys have been a focal point of development, especially for private sector agrarian investment in crop production for export and biodiesel. Agricultural frontiers have expanded, regreening the arid landscapes of dry forests in the northern part of the country, and the desert sand dunes in the south. Industrial agriculture offers a means to diversify the Peruvian economy; but this process has been characterised by land acquisition and concentration by the agro-export producers. At the same time, smallholder parcels are subdivided even further, making it challenging for these people to sustain agrarian livelihoods. We focus here on the Chira Valley, located in the Piura region of northern Peru.

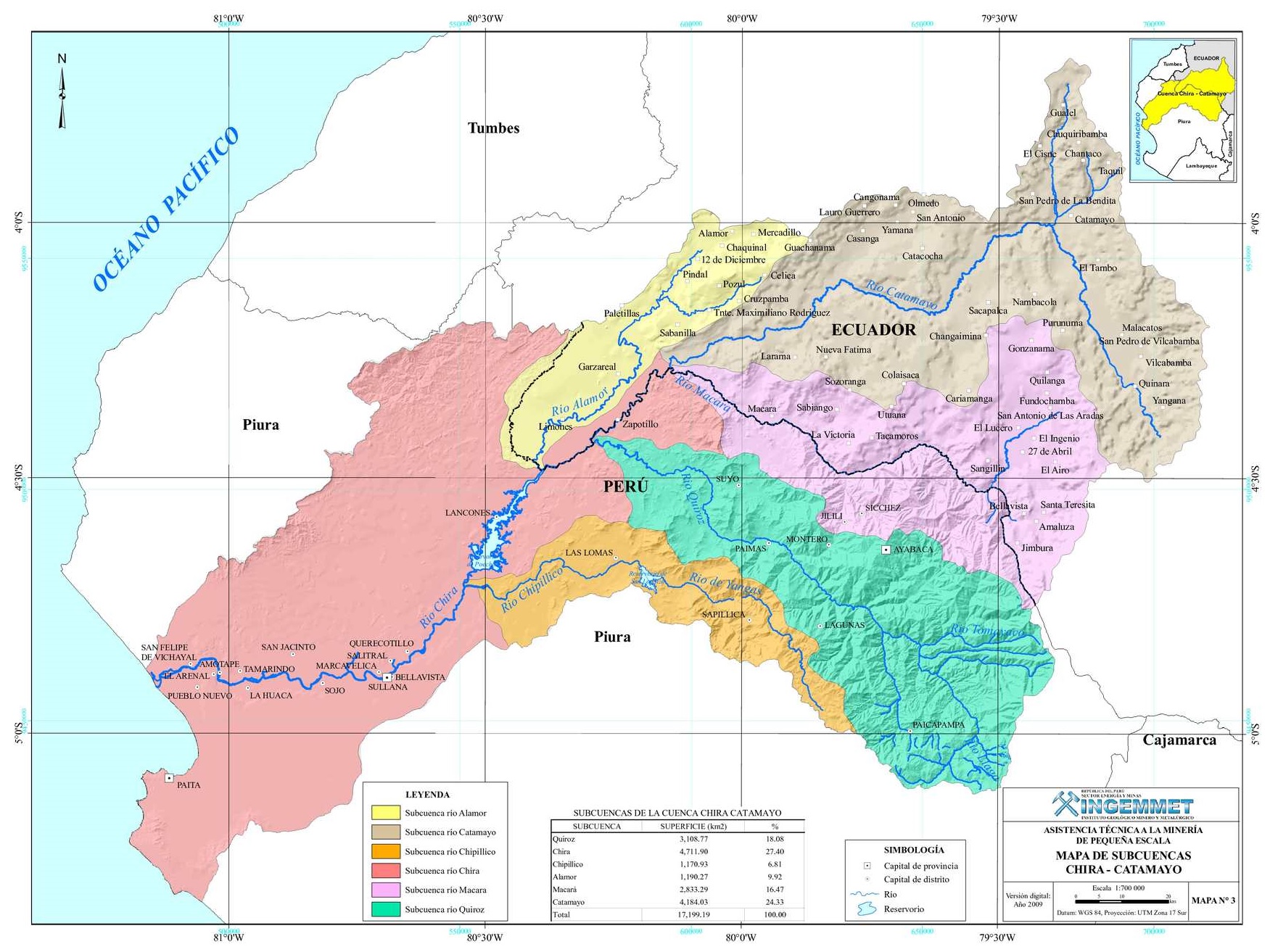

The Chira Valley is located in the low part of Catamayo-Chira binational basin, one of the study regions of the IWSN. In the upper watershed, water flows from the punas of Podocarpus National Park in Ecuador, in the north of Loja Province. The Catamayo River flows from the puna westward toward the Pacific Ocean, and is joined by smaller tributaries until its union with Macará River; here the main course is called the Chira River. The Chira River, along with the Alamor River are dammed in Poechos Reservoir, located in Piura. Water from this reservoir is used for agricultural crop production, hydropower generation, domestic and industrial use (the latter to a lesser extent) in the valleys of Chira and Piura.

The Chira Valley comprises an area of 62,134,89 ha., and currently almost its total area (58,820,96 ha.) is irrigated with more than 937 Hm3 annually with water from the Poechos, one of the largest reservoirs in the country.

As in many coastal valleys in Peru, agricultural water management is organised by irrigation districts. Operation and maintenance of these districts is the responsibility of user groups called Junta de Usuarios, which are divided into smaller sectors called Comisiones de Usuarios (henceforth called “commissions”). These organisations previously included only agrarian water users, but since Peruvian water management institutionalism incorporated the integrated approach, it now involves energetic, industrial, agricultural, and residential users.

The Junta de Usuarios of Chira’s hydraulic sector, in operation since 1973, is made of seven commissions: Miguel Checa, Poechos Pelados, Margen Derecha, Margen Izquierda, Cieneguillo, El Arenal and Daniel Escobar. Of them, the oldest and largest in terms of land area and number of users are Miguel Checa and Margen Derecha. The newest and smallest commission is Daniel Escobar.

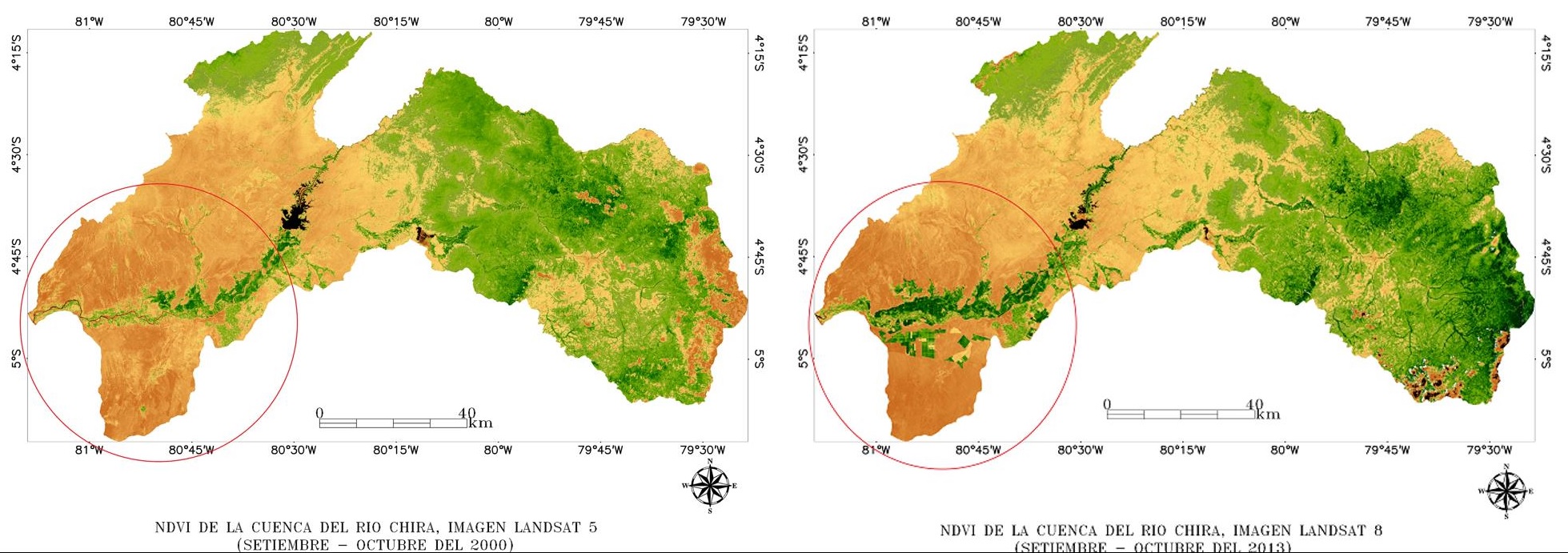

In the Catamayo-Chira basin, the primary economic activity and largest water user has been agriculture, and the current agricultural expansion is intensifying water demands. Since the 1990s, the Peruvian government has promoted land purchase, especially the eriazas, or idle lands, to incorporate them into the Peruvian agro-industrial system. The Chira Valley currently has large areas devoted to the cultivation of sugar cane crops for biodiesel, table grapes, and organic bananas for export through fair trade markets. The latter is driven by producer’s associations and non-governmental organisations. Some traditional rice crops are also maintained (in the past shared with native and pima cotton crops), however many farmers have converted to export crops because of the uncertainty of rice markets and prices.

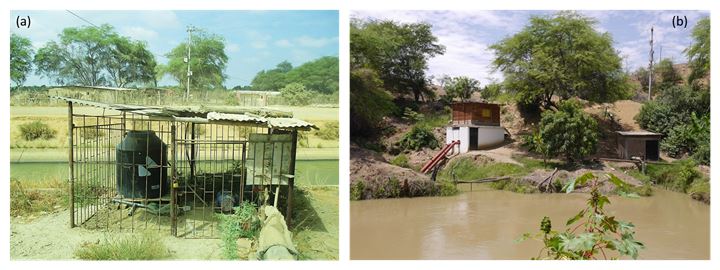

Agricultural expansion is even more evident at the scale of irrigation sectors. As an example, the Daniel Escobar Commission, just ten years before composed of undeveloped desert, now has more of 4000ha of irrigated fields. Farmers have also invested in new technologies to sustain larger scale agriculture under the umbrella of “efficiency.” The commission provides drip systems to farmers at subsidised rates. As an organisation, this commission is investing in technology (such as equipment and software) for better water monitoring and management.

“Since 2010, we decided to elaborate a strategic plan for our organisation [Daniel Escobar Commission]. In the plan we proposed our organisation as credit operators, and nowadays our commission has a saving and loan cooperative without arrearage. […] So farmers in our commission have access to credits and are encouraged to save money. […] Through the cooperative, we are working on a project to improve irrigation systems, from conventional to drip. Also, we have made available 40 drip irrigation modules. As we do not have irrigation channels, we are improving infrastructure through technician irrigation bonds or improving it for efficiency in water consumption. Especially for being efficient and instead irrigate with water pumped by combustion equipment, do it by electric equipment. By these means, we won a contest promoted by FINCyT [Innovation, Science and Technology Fund, from Peru] for water efficient use in lemon crops using evapotranspiration sensors.”

(Mr. Hector, President of Daniel Escobar Commission)

In this context, the National Water Authority (Autoridad Nacional de Agua, ANA), continues a national water rights formalisation process. This effort began in 2004 with the aim of guaranteeing legal security for water access, although in the Chira Valley, water shortages are such that the only type of right that can be granted, called a permiso, is for periods of surplus.

In the midst of the agro-export boom and the financial income it provides to the region, there is heated debate and concern about low water levels in the Poechos Reservoir and deforestation in the upper basin. Constructed in 1976, the Poechos Reservoir had an initial capacity of 1000 millions m3. Today, the reservoir is able to store less than 50% of this capacity because of silt deposition. Proposals to address this problem include the construction of satellite reservoirs and increasing the height of the dam. Nevertheless, these proposals are incomplete since they do not involve actions to stop deforestation in the upper basin or enhance binational dialogue with Ecuador to reach and put into practice agreements to improve sustainable management of the basin according to their common goals.

In addition to the social, political and economic pressures facing the Chira Valley, the El Niño climate cycles also affect water security in the region. When El Niño occurs, lessons learned by previous El Niño events seem to be forgotten – the risk of flooding settlements, the spread of waterborne diseases, crops loss, and infrastructure collapse. This year, 2016, an extraordinary Niño was predicted, and many preventive activities were undertaken, but after a few months and good intentions, small-scale producers are still the most vulnerable and isolated if intense storm systems do occur.

landholders use water pumps for irrigation

Concerns over water scarcity in the basin are still treated largely as speculations; agricultural expansion continues with projects to install crops in new areas. Many of the Piura dry forests are projected to become part of the productive landscape. The expansion continues even in the face of climatic and water supply uncertainty. Although there are important initiatives to conserve and protect the cloud forests in the highest part of the basin, including water funds promoted by farmers, governmental, and non-governmental institutions, there are still many challenges to face and commitments needed to attain regional water security. In the meantime, the agro-export development continues.